トピックス

2017.05.18

OBESITY(英文)

■こちらは、ノールデン氏の文書(英文)です。

<Metabolism and practical medicine>(代謝と実践医療)

THE PATHOLOGY OF METABOLISM(代謝の病理学)

CHAPTER Ⅲ OBESITY(肥満) By Carl von Noorden

Ⅰ. THE ENERGY EXCHANGE(エネルギー交換)

OBESITY is the result of a long-continued disproportion between the amount of fat consumed and that metabolized.

It has already been pointed out that protein may be retained in the body, and may therefore be regarded as a source of gain, although the amount of such protein is usually small, and only becomes large when the calorific value of the food-supply is enormously increased, or when, for other reasons, an energetic cell growth occurs.

With this exception, by far the greater part of that food which is not required for the immediate wants of the tissues goes to enrich the fat depots ; indeed, often the entire quantity of this excess food is thus deposited, the protein remaining practically the same [Pfliiger (1)].

Leaving from our consideration, therefore, the deposition of protein which only takes place under favourable conditions the following facts remain :

The ingestion of a quantity of food greater than that required by the body leads to an accumulation of fat, and to obesity should the disproportion be continued over a considerable period.

From this it follows that obesity may occur as the result of

1. An increased food-supply with normal energy expenditure.

2. A normal food-supply with diminished energy expenditure.

Here one must distinguish between expenditure of energy diminished on account of muscle inactivity and that diminished as the result of a diseased condition of the cells of the body, whereby the oxidation processes are carried out less energetically i.e., a slowing of metabolism.

3. A combination of both conditions.

The extent to which these factors are severally instrumental in causing the various clinical forms of obesity is a question to be dealt with in the special works on pathology [von Noorden (2)]. Here we have only to consider the question whether or not a form of obesity exists which is the result of a diminution in the energy of protoplasmic decomposition, which may therefore be regarded as the result of abnormal metabolism.

1. Obesity Associated with Normal Expenditure.

Clinical experience has shown beyond all doubt that when the amount of actual energy expenditure lies within the normal limits, obesity is due to a long-accustomed but excessive intake of food.

The amount of food consumed, and the nature of that food, afford valuable indications of obesity from such a cause.

Such obese individuals frequently prefer fat-forming or carbohydrate food in which a high calorific value is combined with small volume.

As a rule it is the natural inclination on the part of every human being to maintain his state of nutrition at a constant level, this level being determined by his own free will that is to say, he regulates his food- supply without any precise regard to the actual requirements of his tissues.

Equilibrium is not, of course, maintained at every hour of his life ; at one time, perhaps, the intake is excessive, at another time it is insufficient, but on the whole the general balance is maintained.

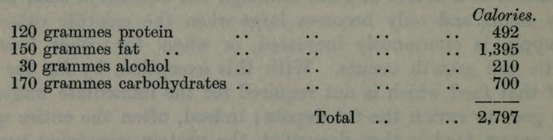

The mean value for the calorific requirements of the body can be calculated from known data. For a healthy individual weighing 70 kilogrammes, engaged in the ordinary duties of life, 40 calories per kilogramme body- weight per diem, making 2,800 calories in all, are required (see discussion on Chittenden's experiments). The calorific supply may be made up as follows :

It is reasonable to suppose that at certain times slight changes may occur in taste, or in choice of food, or in its preparation and quantity, whereby the calorific value of the food may be raised to slightly exceed the mean.

On a diet, for example, containing a little more albumin, fat, and carbohydrate, the calorific value may be increased by 200 while the individual continues to engage in his usual duties.

These 200 calories represent such a small amount of food that neither eyesight nor appetite afford any indication of it, and therefore the person can say to the best of his knowledge that his food-supply has not been altered, although he has obviously become corpulent.

The 200 calories in question are contained in

1/3 litre milk,

200 grammes lean meat,

100 grammes fat meat,

90 grammes rye-bread,

4/10 litre light beer.

Cases in actual life in which the mean calorific value of the food- supply is unknowingly exceeded occur very frequently, and the actual meaning of the small excess of 200 calories per diem may be illustrated by the following calculation :

The entire food excess, with the exception of a small fraction negligible in this calculation, is laid up in the fat depots, 200 calories corresponding to 21-5 grammes fat, so that a total fat accumulation of 7-85 kilogrammes may occur in one year. As the fatty tissues contain water, the increase in weight may be as much as 11 kilogrammes.

The example just cited is characteristic of what occurs very often in every-day life, and is intended to express numerically how, by an insignificant increase in the food over and above the amount actually required by the body, a state of obesity may gradually develop. It shows, further, how large the calorific value, and yet how small the actual amount of the food required may be in order to produce such a state.

There is no fundamental difference between this form of obesity and other forms in which a disproportion between the amount of food supplied and that utilized is brought about by a gradual though incomprehensible diminution in muscular activity.

Such cases are quite as numerous, and these persons become obese as the result of insufficient physical exercise.

This may be due to an inherent desire on the part of the person for ease, or to some infirmity, such as heart failure or disease of the limbs, or it may be the result of a phlegmatic temperament, whereby the individual leads a sedentary indoor life with little or no opportunity for engaging in active work.

Such individuals become less healthy, but not through a diminished capacity on the part of the cells to carry on their oxidation processes.

If the cells were permitted to work, then they would carry out their functions even as extravagantly as those of the normal individual.

If the disinclination for muscular exercise is combined with an increased indulgence in food which is, unfortunately, only too often the case then the danger of undesirable corpulency is, naturally, doubled.

There can be no doubt but that obesity so produced must be regarded as a disease, for the functions of the various organs of the body, in particular those of the vascular system, are damaged, and life may be thereby shortened. One cannot, however, regard this as disordered metabolism, for the metabolism of such obese persons is normal, and remains so ; it is the mode of living which is abnormal (exogenous obesity).

Clinical experience, as well as experimental results, show that this form of obesity is by far the most common. It is generally recognised as such, and the question only remains whether or not a form of obesity occurs which is the result of impaired energy exchange.